The Effect of Immigration on Surnames

The Effect of Immigration on Surnames

Immigrants changed their names by accident or by design. Other languages had letter combinations not found in English, or letters pronounced as other letters in the English language. F sounded like V, so Freer was written Veer. W sounded like V, so Werner was listed as Verner. A guttural pronunciation made G sound like K. Letters were slurred, an H dropped. Sch sounded like Sh, so the c disappeared.

You can get some idea of how names changed and how a name change might affect the immigrant by reading letters culled from records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service at http://uscis.gov/graphics/aboutus/history/articles/ names.htm. They describe situations in which the immigrant's name or that of his sons doesn't match the name on his naturalization papers, so they are not able to vote. In another, the immigrant dropped part of his name at naturalization, and then moved to another city and wanted to reinstate the suffix. These kinds of situations explain why we may have trouble finding our immigrant ancestors.

The Wish to “Sound American”

Occasionally, the immigrant shortened or changed his name, but more often, the children of these immigrants Anglicized their names to better assimilate: Petrasovich became Preston; Noblinski became Noble; Savitch became Savage; Madsen became Madison.

Sometimes finding their names “different,” immigrants chose to translate their names to the English equivalents. Blau and Bleu became Blue; Weiss, Blanc, and Bianco all became White. Occupational names were changed with Schmidts becoming Smiths and Kÿfers becoming Coopers.

If you are unfamiliar with the language of the immigrant, look for a dictionary that has both the foreign language and English. Perhaps the foreign language equivalent for the surname will be the one you need to further your research. Knowing that “Weaver” translates to “Weber” in German may be just the clue you need to find an earlier generation.

A wish to disassociate from “foreigners” made some families make the change. In Pennsylvania, Frank Nicotera felt the pressure of his Italian name. When he married a Collins, he registered at the union hall as Frank Collins. When his little brother was ready to go to work, Frank took him to the union hall where everyone assumed he was Nick Collins, not Angelo Nicotera. The family today goes by the name Collins. The grandchildren are unaware that the family's surname was Nicotera only three generations ago.

Lineage Lessons

There are families in which brothers have different surnames though they have the same father. One has decided to keep the old spelling, whereas the others have adopted a new spelling.

This can lead to two branches of the same family having very different surnames. In another case, a divorce in New York City in the 1820s resulted in the wife resuming her maiden name and her younger children taking that name, whereas the adult children retained the father's name.

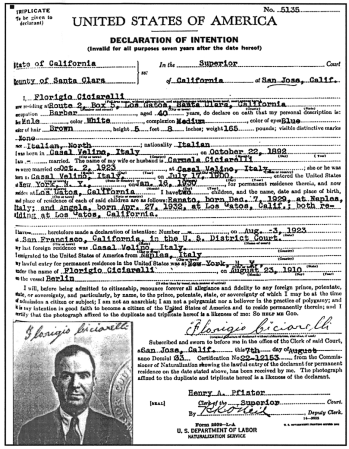

The following sample Declaration of Intention is an example of the name changes that often happened. The subject was born 20 October 1892 in Casal Velino, province of Salerno, Italy, according to his birth certificate, which names him as Florigio Cicerelli. He first immigrated (under that spelling) in 1910 with his father Saverio on the U.S.S. Berlin, arriving in New York City with a destination of San Jose, California. Returning to Italy, he was married under that spelling in 1922 to Carmela Spagnuola. When Florigio returned in 1930 from his fourth and final trip to Italy, the Arrival Certificate in New York shows him as Cicierelli. Three years later, when he filed to become a citizen, his name is shown as Ciciarelli. In the meantime, he also had adopted the more American sounding “Frank,” and was known throughout the rest of his life as Frank Ciciarelli. His children's names bore that spelling, too. Similar changes occurred in thousands of families.

Families make unpredictable decisions that cause research problems for genealogists. Letters are added or dropped. Perhaps the name had a prefix that was later dropped: St. Martin became Martin; Van Hoorn became Horn. A generation later, someone chose to reinstate the suffix. One branch of the family may decide the name would be more aristocratic with a slight change. Even simple names are changed. Names abound where an “e” is added or removed: Brown/Browne, Green/Greene, Germaine/Germain, Low/Lowe.